Paul Kelley for The New York Times

Roald Gundersen built his home and greenhouse using whole tree for structure and support. More Photos >

By ANNE RAVER

Published: November 4, 2009

STODDARD, Wis.

The Forester-Architect

Paul Kelley for The New York Times

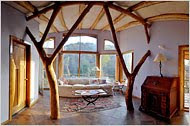

The loft in the Stoddard, Wisc. home of Amelia Baxter and Mr. Gundersen. More Photos »

ROALD GUNDERSEN, an architect who may revolutionize the building industry, shinnied up a slender white ash near his house here on a recent afternoon, hoisting himself higher and higher until the limber trunk began to bend slowly toward the forest floor.

“Look at Papa!” his life and business partner, Amelia Baxter, 31, called to their 3-year-old daughter, Estella, who was crouching in the leaves, reaching for a mushroom. Their son, Cameron, 9 months, was nestled in a sling across Ms. Baxter’s chest.

Wild mushrooms and watercress are among the treasures of this 134-acre forest, but its greatest resource is its small-diameter trees — thousands like the one Mr. Gundersen, 49, was hugging like a monkey.

“Whooh!” he said, jumping to the ground and gingerly rubbing his back. “This isn’t as easy as it used to be. But see how the tree holds the memory of the weight?”

The ash, no more than five inches thick, was still bent toward the ground. Mr. Gundersen will continue to work on it, bending and pruning it over the next few years in this forest which lies about 10 miles east of the Mississippi River and 150 miles northwest of Madison.

Loggers pass over such trees because they are too small to mill, but this forester-architect, who founded Gundersen Design in 1991 and built his first house here two years later, has made a career of working with them.

“Curves are stronger than straight lines,” he explained. “A single arch supporting a roof can laterally brace the building in all directions.”

The firm, recently renamed Whole Tree Architecture and Construction, is also owned by Ms. Baxter, a onetime urban farmer and community organizer with a knack for administration and fundraising. She also manages a community forest project modeled after a community-supported agriculture project, in which paying members harvest sustainable riches like mushrooms, firewood and watercress from these woods, and those who want to build a house can select from about 1,000 trees, inventoried according to species, size and shape, and located with global positioning system coordinates, a living inventory that was paid for with a $150,000 grant from the United States Department of Agriculture.

According to research by the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, run by the USDA, a whole, unmilled tree can support 50 percent more weight than the largest piece of lumber milled from the same tree. So Mr. Gundersen uses small-diameter trees as rafters and framing in his airy structures, and big trees felled by wind, disease or insects as powerful columns and curving beams.

Taking small trees from a crowded stand in the forest is much like thinning carrots in a row: the remaining plants get more light, air and nutrients. Carrots grow longer and straighter; trees get bigger and healthier.

And when the trees are left whole, they sequester carbon. “For every ton of wood, a ton and a half of carbon dioxide is locked up,” he said, whereas producing a ton of steel releases two to five tons of carbon. So the more whole wood is used in place of steel, the less carbon is pumped into the air.

These passive solar structures also need very little or no supplemental heat.

Tom Spaulding, the executive director of Angelic Organics Learning Center, near Rockford, Ill., northwest of Chicago, knows about this because he commissioned Mr. Gundersen to build a 1,600-square-foot training center in 2003. He said: “In the middle of winter, on a 20-below day, we’re in shorts, with the windows and doors open. And we don’t burn a bit of petroleum.”

“It’s eminently more frugal and sustainable than milling trees,” he added. “These are weed trees, so when you take them out, you improve the forest stand and get a building out of it. You haven’t stripped an entire hillside out west to build it, or used a lot of oil to transport the lumber.”

Mr. Gundersen had a rough feeling for all of this 16 years ago, when he started building a simple A-frame house here for his first wife and their son, Ian, now 15. He wanted to encourage local farmers to use materials like wood and straw from their own farms to build low-cost, energy-efficient structures. So he used small aspens that were crowding out young oaks nearby.

“I would just carry them home and peel them,” said Mr. Gundersen, who later realized he could peel them while they were standing, making them “a lot lighter to haul and not so dangerous to fell.”

Mr. Gundersen, who built most of the house singlehandedly, also recognized the beauty of large trees downed by disease or wind, and used the peeled trunks, shorn of their central branches a few feet from the crook, as supporting columns in the house. “I thought they were beautiful, but I didn’t think how strong they were,” he said.

... (more)

No comments:

Post a Comment